Caste and Human Trafficking

Caste discrimination affects an estimated 260 million people worldwide, the vast majority of whom live in South Asia. Within the caste system, the Dalits or untouchables are believed to be inherently impure, such that it is unacceptable to be in close physical proximity with them. Touching anything they may have touched or walking on a path where they may have walked is believed to contaminate or pollute someone of a higher caste.

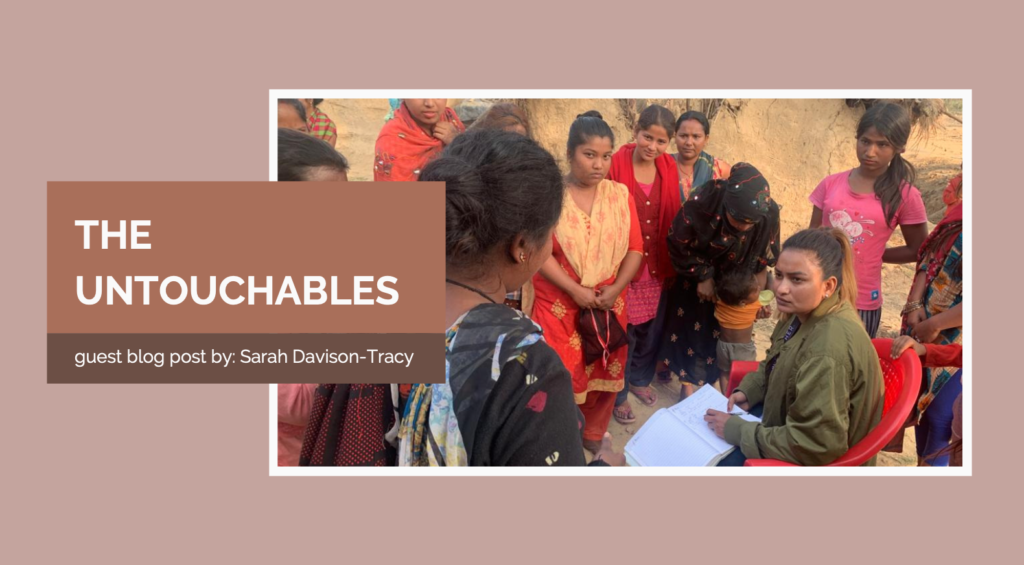

Among the Dalits, there are levels of hierarchy as well. Sometimes called the dust of Nepal or the untouchables of the untouchables, the lowest of all among the Dalits are the Badi. For hundreds of years, the Badi made their living as entertainers, performing songs and dances and telling stories at festivals, weddings, and private parties. Badi translates to “musical people,” and they were often sought-after musicians, singers, and dancers.

In the 1950s, several events occurred that impacted the livelihoods of the Badi and catapulted them into extreme poverty that has continued to this day. In 1951, the Rana oligarchy ended in Nepal, which created a cascading ripple effect that shifted power structures and reduced opportunities for work among the Badi and other low-caste communities. Two other significant factors entered the mix in the 1960s: the population increased in the far west of Nepal, where the Badi were located, and access to radio and television for entertainment expanded. As jobs became harder to come by and the Badi were less frequently employed for entertainment, poverty expanded and deepened. To compensate for their significant loss in employment, Badi women began to more frequently and openly turn to prostitution for their livelihood.

The Badi have had little to no access to education, healthcare, land ownership, and citizenship. Most Badi are illiterate. Teachers and higher-caste children have frequently banned Badi and other low-caste Dalit children from their classrooms. Until this generation, no known Badi children ever progressed beyond the sixth grade.

One-third of Badi are homeless, and two-thirds are living on public or government land. Nearly 75 percent of Badi men migrate to search for search for employment, leaving women and children to fend for themselves.

These complex and far-reaching factors have created the devastating reality that prostitution and selling girls to traffickers have become sources of income for many Badi families. Even while a woman is pregnant, it is common for her to be approached by a trafficker, who offers her a deposit in exchange for the promise that if she gives birth to a girl, that girl will be sold to the trafficker. Generally, when the girl is around ten years old, the trafficker will return for the girl, pay the family, and take her to a brothel where she is enslaved as a sex worker—mostly likely, for the rest of her life.

The Badi are perfect human trafficking targets: vulnerable, desperate, and, according to many, the worthless dust of Nepal.

Human trafficking is a heartbreaking—and potentially overwhelming—reality that has impacted not only the Badi, but millions more around the world. Globally, the statistics for the total number of people trafficked vary greatly—by millions. The most frequent source cited by international human rights organizations is the International Labour Organization (ILO), which reported that in 2016, 40.3 million people were victims of modern slavery and that one in four of those victims were children. Furthermore, the ILO documents that in 2016, 4.8 million people were in forced sexual exploitation, and of that number, 99 percent were women. They estimate that human trafficking generates about $150 billion a year in revenue. Human trafficking ranks third in organized crime, after the sale of arms and drugs.

In Nepal, it is estimated that 15,000 women and 5,000 girls each year are trafficked out of the country for the purpose of sexual exploitation and profit. Many are trafficked before they reach ten years old since virgins and young girls are more profitable. Once sold, a girl is forced to stay until her purchase price, often called her “debt,” is paid back. It is a nearly impossible task, and most never repay their debt or leave the brothel.

Most girls never live to tell what happened to them in the brothels. Of those who do escape, very few speak of the terrors they experienced. But there is hope…

– Sarah Davison-Tracy

To learn more and be inspired by stories of heroism & hope, Click HERE to purchase Sarah Davison-Tracy and Devisara Badi’s book, No Longer Untouchable.

To dive deeper into the conversation, register for our upcoming virtual event >